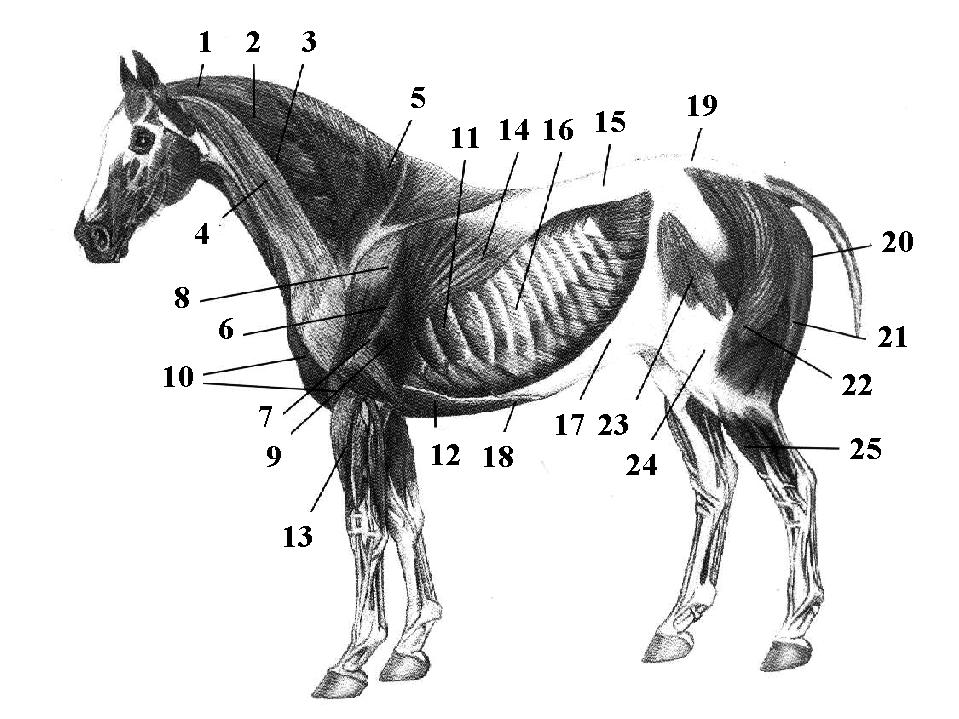

Conformation Components

Excerpt from

Horse for Sale, How to Buy a Horse or Sell the One You Have

by Cherry Hill © 1995

Balance

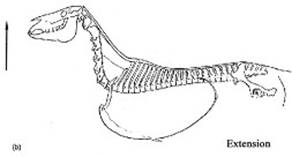

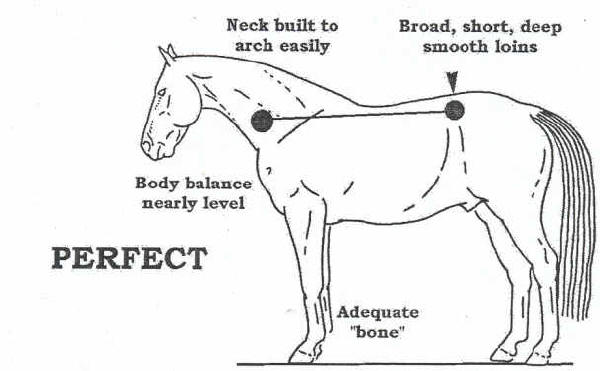

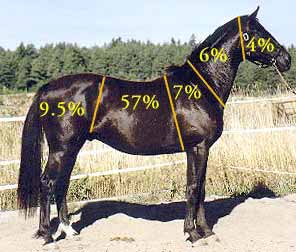

A well-balanced horse has a better chance of moving efficiently with less stress. Balance refers to the relationship between the forehand and hindquarters, between the limbs and the trunk of the body, and between the right and the left sides of the horse.

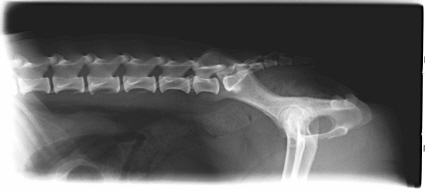

The center of gravity is a theoretical point in the horse's body around which the mass of the horse is equally distributed. At a standstill, the center of gravity is the point of intersection of a vertical line dropped from the highest point of the withers and a line from the point of the shoulder to the point of the buttock. This usually is a spot behind the elbow and about two thirds the distance down from the topline of the back.

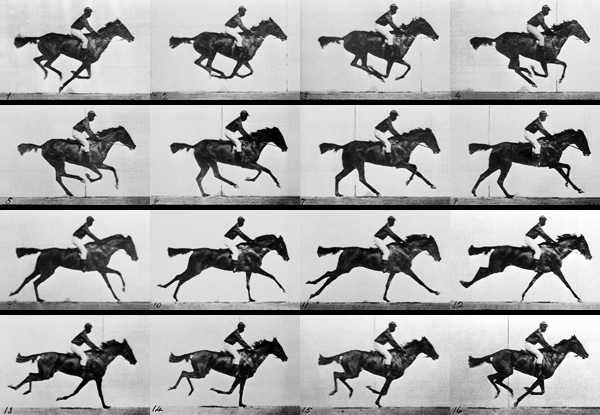

Although the center of gravity remains relatively constant when a well-balanced horse moves, most horses must learn to rebalance their weight (and that of the rider and tack) when ridden. In order to simply pick up a front foot to step forward, the horse must shift his weight rearward. How much the weight must shift to the hindquarters depends on the horse's conformation, the position of the rider, the gait, the degree of collection, and the style of the performance. The more a horse collects, the more he steps under his center of gravity with his hind limbs.

If the forehand is proportionately larger than the hindquarters, especially if it is associated with a downhill topline, the horse's center of gravity tends to be forward. This causes the horse to travel heavy on his front feet, setting the stage for increased concussion, stress, and lameness. When the forehand and hindquarters are balanced and the withers are level with or higher than the level of the croup, the horse's center of gravity is located more rearward. Such a horse can carry more weight with his hindquarters, thus move in balance and exhibit a lighter, freer motion with his forehand than the horse with withers lower than the croup.

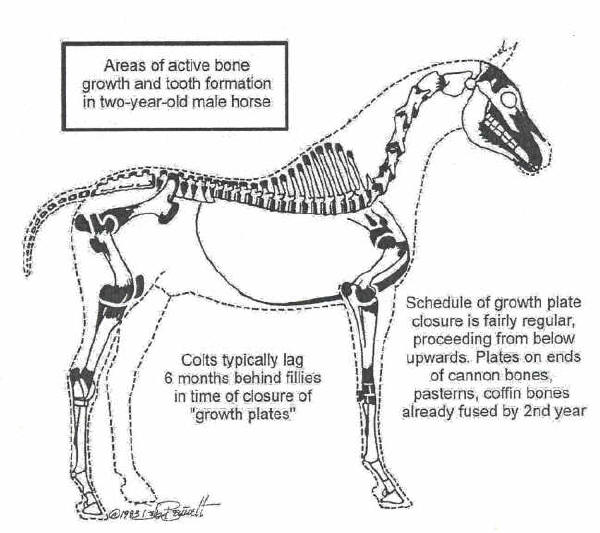

When evaluating yearlings, take into consideration the growth spurts which result in a temporarily uneven topline. However, be suspicious of a two-year-old that show an extreme downhill configuration. Even if a horse's topline is level, if he has an excessively heavily muscled forehand in comparison to his hindquarters, he is probably going to travel heavy on the forehand and have difficulty moving forward freely.

A balanced horse has approximately equal lower limb (front) length and depth of body. The lower limb length (chest floor to the ground) should be equal to the distance from the chest floor to the top of the withers. Proportionately shorter lower limbs are associated with a choppy stride.

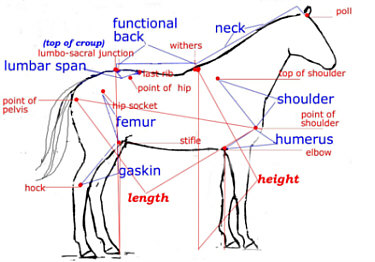

The horse's height or overall limb length (point of withers to ground) should approximate the length of the horse's body (the point of the shoulder to the point of buttock). A horse with a body a great deal longer than its height often experiences difficulty in synchronization and coordination of movement. A horse with limbs proportionately longer than the body may be predisposed to forging, over-reaching and other gait defects.

When viewing a horse overall, the right side of the horse should be symmetric to the left side.

Proportions and Curvature of the Topline

The ratio of the topline's components, the curvature of the topline, the strength of loin, the sharpness of withers, the slope to the croup, and the length of the underline in relation to the length of back all affect a horse's movement.

The neck is measured from the poll to the highest point of the withers. The back measurement is taken from the withers to the loin located above the last rib and in front of the pelvis. The hip length is measured from the loin to the point of buttock.

A neck that is shorter than the back tends to decrease a horse's overall flexibility and balance. Be sure to look at the neck from both sides because the mane side often appears shorter than the non-mane side. A back that is a great deal longer than the neck tends to hollow. A very short hip, in relation to the neck or back, is associated with lack of propulsion and often a downhill configuration. A rule of thumb is that the neck should be greater than or equal to the back and that the hip should be at least two-thirds the length of the back.

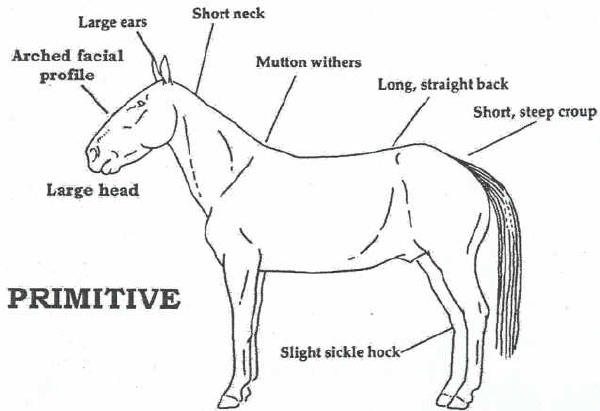

The neck should have a graceful shape that rises up out of the withers, not dip downward in front of the withers. The upward curve to the neck should be more pronounced in a dressage prospect than in a hunter or western prospect. The shape of the neck is determined by the S shape formed by the seven cervical vertebrae. A longer, flatter (more horizontal) configuration to the upper vertebrae results in a smoother attachment at the poll (as if the neck is behind the skull or the head is attached on the end of a flexible balancing arm) and results in a cleaner, more supple throat latch. If the upper vertebrae form a short, diagonal line to the skull, it is associated with an abrupt attachment (as if the neck attaches below the skull or the head is stuck on top of the neck) resulting in a thick throat latch, lack of flexibility, and possibly a hammerhead.

The curve to the lower neck vertebrae should be short and shallow and attach relatively high on the horse's chest. The thickest point in the neck is at the base of the lower curve. Ewe necked horses often have necks that have a undesirable long, deep lower curve and attach low to the chest. The attachment of the neck to the shoulder should be smooth without an abnormal dip in front of the shoulder blade.

The upper neck length (poll to withers) should be at least twice the lower neck length (throat latch to chest). This is dictated to a large degree by the slope of the shoulder. A horse with a very steep shoulder has an undesirable ratio (approaching 1:1) between the upper neck length and lower neck length. The more sloping the shoulder, the longer the neck's top line becomes and the shorter the neck's underline. The muscling of the topline of the neck should be more developed than the muscling of the underside of the neck. A thick underside to the neck is associated with a horse that braces against the bit and hollow's the neck's top line.

The back should look like it has a natural place for a saddle beginning with prominent withers that are located above or slightly behind (but not exaggeratedly in front of) the heart girth. The heart girth is the circumference of the barrel just behind the front limbs. The withers should gradually blend into the back ideally ending just in front of the midpoint of the back. The withers provide a place for the neck muscles and ligamentum nuchae to anchor and they should attach at the highest point of the withers; there should not be a dip in front of or behind the withers.

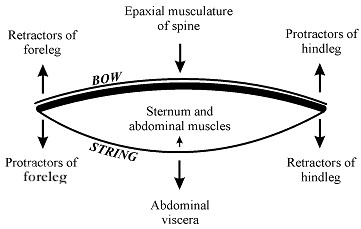

The withers also act as a fulcrum. As a horse lowers and extends its neck, the back rises. Low, mutton withers limit a horse's ability to raise his back. A horse with a well-sloped shoulder usually has correctly-placed withers. The heart girth should be deep which indicates adequate room for the heart and lungs.

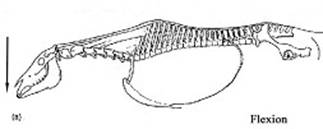

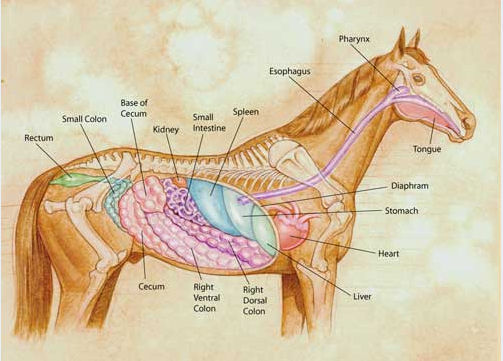

The muscles that run alongside the spine should be flat and strong rather than sloped or weak. The back muscles must help counteract the gravitational pull from the weight of the horse's intestines as well as support the rider's weight. The line of the back should be flat or level, not hollow (dipped or concave) or roached (bowed up or convex). A hollow back is associated with weakness and a roached back with stiffness.

The loin is located along the lumbar vertebrae from the last rib-bearing (dorsal) vertebrae to the lumbosacral joint. The loin should be well muscled and relatively short. Horses termed "long-backed" often have an acceptable back length but a long, weak loin. A horse with a weak and/or long loin and loose coupling tends to have a hollow back. (The coupling is the area behind the last rib and in front of a vertical line dropped from the point of hip.) A horse that chronically hollows its back may be predisposed to back problems.

The loin and the coupling are what transfer the motion of the hindquarters up through the back and forward to the forehand, so they must be strong and well connected. A short, heavily muscled loin has great potential strength, power, and durability yet could lack the flexibility that a more moderately muscled loin may have. Loin muscling (best viewed from the top) should appear springy and resilient not stiff and cramped or weak and saggy. A lumpy appearance in the loin area may indicate partial dislocations of the vertebrae.

The croup is measured from the lumbosacral joint (approximately indicated by the peak above and slightly behind the points of hip) to the tail head. The croup should be fairly long as this is associated with a good length to the hip and a desirable, forward-placed lumbosacral joint. The slope to the croup will depend on the breed and use. Quarter Horses and Thoroughbreds traditionally have round croups; Arabs and Warmbloods have flat croups.

The topline should be "short" relative to the underline. Such a combination indicates strength plus desirable length of stride.

Head

The head should be functionally sound. The brain coordinates the horse's movements, so adequate cranial space is necessary. The length from the base of the ear to the eye should be at least 1/3 the distance from ear to nostril. The width between the eyes should be a similar distance as that from the base of the ear to the eye. A wide poll with ears far apart is associated with the atlas connecting behind the skull rather than below it. A wide open throat latch allows proper breathing during flexion; a narrow throat latch is often associated with a ewe-neck attachment. Eyes set off to the side of the head allow the horse to have a panoramic view. The eye should be prominent without bulging. Prominence refers to the bony eye socket, not a protruding eyeball. The expression of the eye should indicate a quiet, tractable temperament.

The muzzle can be trim, but if it is too small, the nostrils may be pinched and there may be inadequate space for the incisors resulting in dental misalignments. The incisors should meet evenly with no overhang of the upper incisors (parrot mouth) or jutting out of lower incisors. The width of the cheek bones indicates the space for molars; adequate room is required for the sideways grinding of food. The shape of the nasal bone and forehead is largely a matter of breed and personal preference.

Quality

Quality is depicted by "flat" bone (indicated by the cannon bone), clean joints, sharply defined (refined) features, smooth muscling, overall blending of parts, and a fine, smooth hair coat. "Flat" bone is a misnomer because the cannon bone is round. Flat actually refers to well-defined tendons that stand out cleanly behind the cannon bone and give the impression the bone is "flat".

Substance refers to thickness, depth, and breadth of bone, muscle, and other tissues. Muscle substance is described by type of muscle, thickness of muscle, length of muscles, and position of attachment. Other substance factors include weight of the horse, height of the horse, size of the hoofs, depth of the heart girth and flank, and spring of rib.

Best viewed from the rear, spring of rib refers to the curve of the ribs; a flat-ribbed horse may have inadequate heart and lung space. Besides providing room for the heart, lungs, and digestive tract, a well-sprung rib cage provides a natural, comfortable place for a rider's legs. A slab-sided horse with a shallow heart girth is difficult to sit properly; an extremely wide-barreled horse can be stressful to the rider's legs.

Substance of bone indicates adequacy of the ratio of the bone to the horse's body weight. Bone measurement is taken on an adult horse around the circumference of the cannon bone just below the knee. For riding horses, an adequate ratio is approximately .7 inches of bone for every 100# of body weight. Using that thumb rule, a 1200 # horse should have an 8.4 inch circumference cannon bone for his weight to be adequately supported.

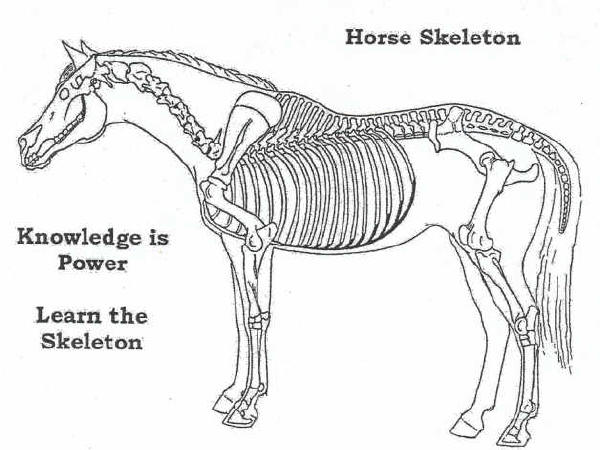

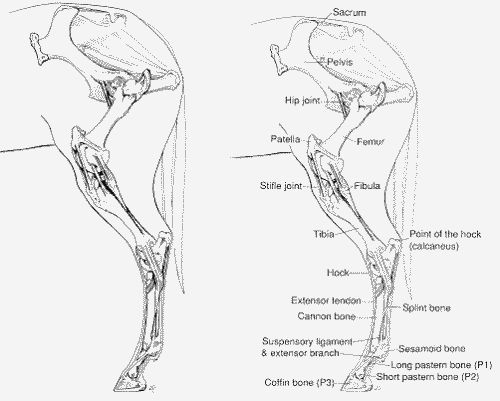

Correctness of Angles and Structures The correct alignment of the skeletal components provides the framework for muscular attachments. The length and slope to the shoulder, arm, forearm, croup, hip, stifle, and pasterns should be moderate and work well together. There should be a straight alignment of bones and large clean joints when viewed from front and rear.

Forelimbs

Both forelimbs should appear to be of equal length and size and to bear equal weight. A line dropped from the point of the shoulder to the ground should bisect the limb. The toes should point forward and the feet should be as far apart on the ground as the limbs are at their origin in the chest. (See Movement for deviations) The shoulder should be well-muscled without being heavy and coarse.

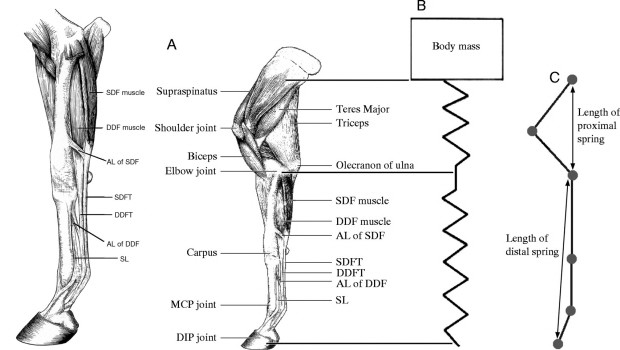

The muscles running along the inside and outside of the forearm should go all the way to the knee, ending in a gradual taper, rather than ending abruptly a few inches above the knee. It is generally felt that this will allow the horse to use its front limbs in a smooth sweeping, forward motion. The pectoral muscles at the horse's chest floor (an inverted V) should also reach far down on to the limb. These and the forearm muscles help a horse move its limbs laterally and medially as well as to elevate the forehand.

Front limbs, when viewed from the side should exhibit a composite of moderate angles, so that shock absorption will be efficient. The shoulder angle is measured along the spine of the scapula from the point of the shoulder to the point of the withers. The shorter and straighter the shoulder, the shorter and quicker the stride and the more stress and concussion transmitted to the limb. Also important is the angle the shoulder makes with the arm (which should be at least 90 degrees) and the angle of the pastern.

The length of the humerus (point of shoulder to the point of elbow) affects stride length. A long humerus is associated with a long reaching stride and good lateral ability; a short humerus with a short choppy stride and poor lateral ability. The steeper the angle of the humerus, generally, the higher the action; the more toward horizontal, the lower the action.

To evaluate the medial-lateral slope of the humerus from the front, find the left point of shoulder and (a spot in front of) the left point of elbow. Do the same on the right side. Connect the four points. If the resulting box is square, the humerus lies in an ideal position for straight lower limbs and straight travel. If the bottom of the box is wider, the horse may toe in and travel with loose elbows and paddle. If the bottom of the box is narrower, the horse will likely toe out, have tight elbows and wing in.

The way the shoulder blade and arm (humerus) are conformed and attach to the chest dictate, to a large degree, the alignment of the lower limbs. Whether the toes point in or out is often a result of upper limb structures. That is why it is dangerous in many cases to attempt to alter a limb's structure and alignment through radical hoof adjustments. When assessing the lower limbs, be sure the horse is standing square.

The knees should be large and clean, not small and puffy. The bone column should be functionally straight and sound, not buck-kneed (over-at-the-knee) or calf-kneed (back-at-the-knee). The calf-kneed horse suffers strain at the back of the knee and concussion at the front of the knee which can result in carpal chips and other problems. The buck-kneed horse is unstable as the knees shake and are on the verge of buckling forward.

The flexor tendons running behind the cannon bone should be even and straight, not pinched in (tied-in) at the back of the knee or lumpy (indicating possible bowed tendon) anywhere from the knee to the fetlock.

Normal front pastern angles range from 53 to 58 degrees. Exceptionally long, sloping pasterns can result in tendon strain, bowed tendon, and damaged proximal sesamoids. Short, upright pasterns deliver greater concussive stresses to fetlock and pastern joints which may result in osselets, ringbone, and possibly navicular syndrome. Fetlock joints should be large enough to allow free movement but they should be devoid of any puffiness. The hoof should be appropriate for the size of the horse, well-shaped and symmetric with high quality hoof horn, adequate height and width of heel, and a concave sole. The hoof angle should be the same as the pastern angle making a smooth continuous line. For more information on hoof conformation and management see

Maximum Hoof Power

(http://www.horsekeeping.com/horse_books/Maximum_Hoof_Power.htm)

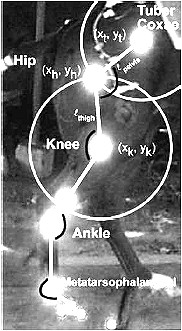

Hind limbs

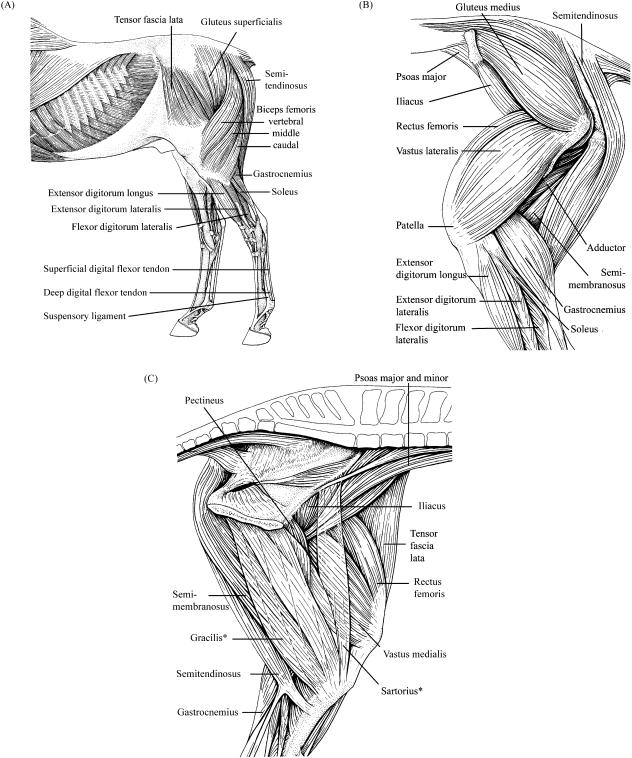

The bone structure and muscling of the hind limb should be appropriate for the intended use. Endurance horses are characterized by longer, flatter muscles; stock horses by shorter, thicker muscles; all-around horses by moderate muscles.

Hind limbs, when viewed from the side should exhibit a composite of moderate angles, so that shock absorption will be efficient. A line from the point of buttock to the ground should touch the hock and end slightly behind the bulbs of the heels. A hind limb in front of this line is often sickle hocked; a hind limb behind this line is often post-legged or camped out.

The hindquarter should be symmetric and well connected to the barrel and the lower limb. The gluteals should tie well forward into the back. The hamstrings should tie down low into the Achilles tendon of the hock.

The relationship of the length of the bones, the angles of the joints, and the overall height of the hind limb will dictate the type of action and the amount of power produced. The length and slope to the pelvis (croup) is measured from the point of hip to the point of buttock. A flat, level croup is associated with hind limb action that occurs behind the hindquarters rather than underneath it. A goose rump is a very steep croup that places the hind limbs so far under the horse's belly that structural problems may occur due to the over-angulation.

A short femur is associated with the short, rapid stride characteristic of a sprinter. A long femur results in a stride with more reach. High hocks are associated with snappy hock action and a difficulty getting the hocks under the body. Low hocks tend to have a smoother hock action and the horse usually has an easier time getting the hocks under the body. The gaskin length (stifle to hock) should be shorter than the femur length (buttock to stifle). A gaskin longer than the femur tends to be associated with cow hocks and sickle hocks.

Hind limbs with open angles (a "straighter" hind limb when viewed from the side) have a shorter overall limb length and produce efficient movement suitable for hunters or race horses. Hind limbs with more closed joints (more angulation to the hind limb) have a longer overall limb length and produce a more vertical, folding action necessary for the collection characteristic of a high level dressage horse. If the overall limb length is too long, however, it can be associated with either camped out or sickle hocked conformation. No matter what the hind limb conformation is at rest, however, it is the way which it connects to the loin and operates in motion that is most important.

From the rear, both hind limbs should appear symmetric, to be of the same length and to bear equal weight. A left to right symmetry should be evident between the peaks of the croup, the points of the hip, the points of the buttock, and the midline position of the tail. The widest point of the hindquarters should be the width between the stifles. A line dropped from the point of the buttock to the ground will essentially bisect the limb but hind limbs are not designed to point absolutely straight forward. It is necessary and normal for the stifles to point slightly outward in order to clear the horse's belly. This causes the points of the hocks to face slightly inward and the toes to point outward to the same degree. The rounder the belly and/or the shorter the loin and coupling, the more the stifles must point out so the more the points of the hocks will appear to point inward. The more slab-sided and/or longer coupled a horse, the more straight ahead the stifles and hocks can point. When the cannon bone faces outward, the horse is often cow-hocked; when cannons face inward, bow-legged.

Soundness problems can occur when the hocks point absolutely straight ahead and the hooves toe out; then there is stress on the hock and fetlock joints. The hind feet should be as far apart on the ground as the limbs are at their origin in the hip. Normal pastern angles for the hind range from 55 to 60 degrees.

http://www.horsekeeping.com/horse_conformation/components.htm

QUESTION

Subj: Gait of Foxtrotters

Date: 98-04-14 18:21:47EDT

From: TRVNKNLS

To: MFTHorses

Perhaps you could direct this question to Ms. Zeigler, who seems to have lots of knowledge on horse gaits, etc. A recently published article on Foxtrotting show horses said that when the show Foxtrotter walks, and foxtrots, it does not bend at the knee. Is that possible ? It seems that a stiff front leg would not give as smooth a ride, and would also subject those horses to be "stumbley" on the trail, or flat dangerous in rough terrain. It seems that in the long run, this type of movement would be detrimental to the breed as a trail and pleasure riding horse. Your thoughts....

ANSWER

In answer to the question on bending the knee at the fox trot. Of course they bend at the knee, they could not move their legs if they did not! I believe that what the writer was trying to say was that Fox Trotters do not have high knee action, and tend to reach "out" rather than "up" with their front legs. This type of leg use in front is different from that of the typical Tennesee Walker or Saddlebred, for example, but similar to that of a Tbred or good moving Quarter Horse.

For this reason, good conformation in the front quarters of a Fox Trotter should include a long, well sloped shoulder and a long, more horizontal than vertical humerus. This predisposes to reach rather than action. In a TWH, however, an upright shoulder and more vertical humerus are desireable because they will predispose to high, short action in front.

The humerus bone is; " the bone running from the front point of the shoulder to the elbow"

Hope this answers the question.

Lee Ziegler

http://www.leeziegler.com

Croup. The croup is of fundamental importance in animal mechanics, because it is the corner-stone of the transmission of the posterior impulse (hocks) to the anterior, and its inclination (according to the axis of the coxa) is directly correlated to the length of the posterior muscles (gluteals and ischeo-tibials) and hence to their angulation. In fact, the femur forms an angle with the coxa which varies from 90° to 120°, and since the metatarsal is always perpendicular to the ground, it is obvious that the inclination of the thigh (femur) and leg (tibia) will depend upon the slope of the croup. We will discuss this further in the section on hindquarters.

A horizontal croup, typical of gallopers, presupposes long ischio-tibial muscles with a consequently greater ability to contract, and thus an ample oscillation of the limbs. An inclined croup, typical of trotters, presupposes shorter muscles. In the Cane corso the croup is slightly inclined: in fact, its typical gait is a lengthened trot.

The croup should be long, because it acts as the fulcrum of transmission; the efficiency of action is in relation to its length.

The width of the croup is in relation to the schelectric construction, and consequently to the development of the muscular mass. The croup of the Cane Corso must be broad because he must develop more power than speed.

A serious fault is a steep croup (over 35°) since it means an insufficiently angulated posterior, caused by the shortening and weakening of the ischio-tibial muscles; the dog, to avoid fatigue, puts one bone radius over the other as vertically as possible with incorrect articulation of the coxofemural and the knee. This pathology often goes with a croup which is higher than the withers and with an excessive weight on the anterior, causing a difficult and clumsy movement. Just as bad but rarer is a horizontal croup (under 15°) which determines a femur-tibial straightening and angles which are too open (If this is associated with a short croup, movement is seriously limited).

Tail. When the Cane Corso relaxes his tail it should look like the backbone of a fish. Being wide at the root and narrowing toward the end, the adipose tissues which cover the caudal vertebrae, resting on the buttocks, give it this characteristic "V" shape. A low-set tail usually goes with a sloping croup. If the tail is too narrow at the root it will be held candle-like in action, and this too should be penalized.

http://www.deucalions.com/standard_comments.htm

Some horses may get exciteable and strong in the gallop and in this case it can help to bridge your reins, as this gives you a secure contact. Bridging your reins means once the rein has passed between your thumb and fore finger it goes across the horse's neck to your other hand where it is held between your thumb and forefinger. You can do this with one or both reins. Keep your hands low, resting them on the horse's neck if you wish.

Some horses may get exciteable and strong in the gallop and in this case it can help to bridge your reins, as this gives you a secure contact. Bridging your reins means once the rein has passed between your thumb and fore finger it goes across the horse's neck to your other hand where it is held between your thumb and forefinger. You can do this with one or both reins. Keep your hands low, resting them on the horse's neck if you wish.

ring or on park trails. This difference is seen in trotting breeds as well. The dressage athletes have longer hind limbs so they can extend at the trot, and an overstride at the walk is of value.

ring or on park trails. This difference is seen in trotting breeds as well. The dressage athletes have longer hind limbs so they can extend at the trot, and an overstride at the walk is of value.

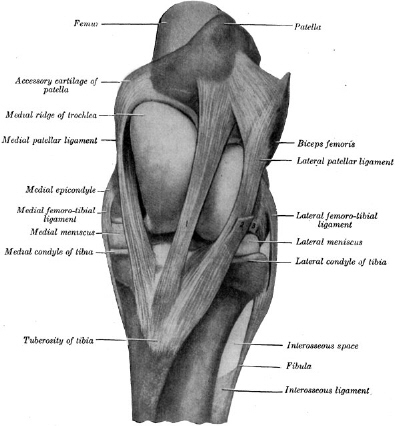

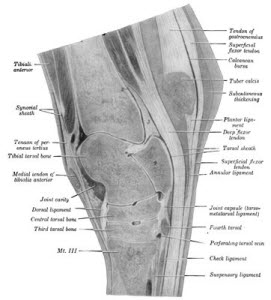

Parts of the outer layer of some joint capsules are thickened to form ligaments. Ligaments connect bone to bone while tendons connect muscle to bone (Figure 1).

Parts of the outer layer of some joint capsules are thickened to form ligaments. Ligaments connect bone to bone while tendons connect muscle to bone (Figure 1). Joint mice are pieces of bone or cartilage found within the joint cavity and may be the result of a fracture. These produce pain when lodged between the articular surfaces and may also produce arthritis. Surgical removal is usually successful (Figure 2).

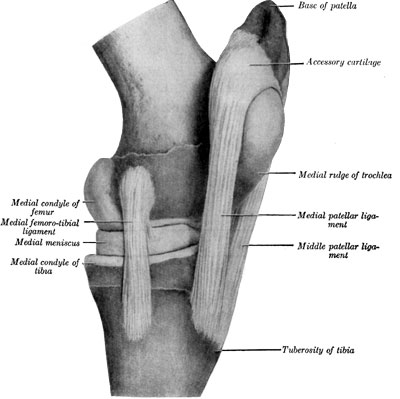

Joint mice are pieces of bone or cartilage found within the joint cavity and may be the result of a fracture. These produce pain when lodged between the articular surfaces and may also produce arthritis. Surgical removal is usually successful (Figure 2). The stifle joint is locked in an extended or straightened stiff position whenever the horse is unable to "unlock" the loop of ligaments from over the bony projection. Sometimes a slap on the croup will cause the horse to jump and "unlock" the stifle joint. Often his "locking" will reoccur. Whenever surgery is necessary to correct the condition, the medial patellar ligament is cut on the inside of the stifle joint in order to prevent further "locking" (Figure 3).

The stifle joint is locked in an extended or straightened stiff position whenever the horse is unable to "unlock" the loop of ligaments from over the bony projection. Sometimes a slap on the croup will cause the horse to jump and "unlock" the stifle joint. Often his "locking" will reoccur. Whenever surgery is necessary to correct the condition, the medial patellar ligament is cut on the inside of the stifle joint in order to prevent further "locking" (Figure 3). Bone spavin is defined as an inflammation of one or more bones of the hock andmost often causes an arthritic condition of the affected bones. In bone spavin the joint between the bones on the inside of the hock become immovable. Quick stops,such as those which occur during roping and other stresses, along with mineral deficiencies, may produce bone spavin. Horses with full, well-developed hocks tend to have less incidence of bone spavin than those with narrow, thin hocks. Bone spavin occurs on the inside of the hock (jack spavin). It may occur between the bones within the hock joint and cannot be seen or palpated (blind spavin). A large percentage of horses affected with blind spavin recover completely.

Bone spavin is defined as an inflammation of one or more bones of the hock andmost often causes an arthritic condition of the affected bones. In bone spavin the joint between the bones on the inside of the hock become immovable. Quick stops,such as those which occur during roping and other stresses, along with mineral deficiencies, may produce bone spavin. Horses with full, well-developed hocks tend to have less incidence of bone spavin than those with narrow, thin hocks. Bone spavin occurs on the inside of the hock (jack spavin). It may occur between the bones within the hock joint and cannot be seen or palpated (blind spavin). A large percentage of horses affected with blind spavin recover completely.

The cause may be due to nutritional deficiencies, accidental injury to the hock joint or the hocks being too straight (hereditary). If the condition is caused by conformation or too straight hocks, it cannot be treated successfully. Veterinarians have many factors to consider in order to determine the cause and to advise the best treatment. Anti-inflammatory drugs may help bog spavin caused by nutritional deficiencies or injury. The drugs decrease inflammation and prevent swelling of the joint capsule. A bandage around the hock prevents excessive build-up of fluid and swelling. The horse is rested for 4 to 6 weeks. Adding vitamins and minerals to the diet may relieve bog spavin. Horses 6 months to 2 years of age are most often affected with bog spavin.

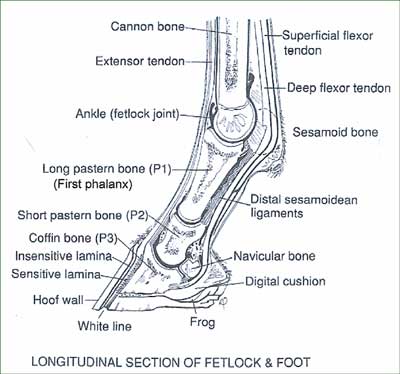

The cause may be due to nutritional deficiencies, accidental injury to the hock joint or the hocks being too straight (hereditary). If the condition is caused by conformation or too straight hocks, it cannot be treated successfully. Veterinarians have many factors to consider in order to determine the cause and to advise the best treatment. Anti-inflammatory drugs may help bog spavin caused by nutritional deficiencies or injury. The drugs decrease inflammation and prevent swelling of the joint capsule. A bandage around the hock prevents excessive build-up of fluid and swelling. The horse is rested for 4 to 6 weeks. Adding vitamins and minerals to the diet may relieve bog spavin. Horses 6 months to 2 years of age are most often affected with bog spavin. This condition is characterized by new bone growth which occurs on the first, second or third phalanx (high or low ringbone). The phalanges are the three small bones extending from the fetlock to the hoof (Figure 7).Ringbone is more common on the forefeet than the hindfeet.

This condition is characterized by new bone growth which occurs on the first, second or third phalanx (high or low ringbone). The phalanges are the three small bones extending from the fetlock to the hoof (Figure 7).Ringbone is more common on the forefeet than the hindfeet. If so, and there is a net loss of energy from moving from A to B too rapidly, or too slowly, then there is most likely a happy mean where it moves from A to B at some optimum speed that maximizes net energy gain. And this optimum might be called the natural speed of motion, or the natural pace of work - where the 'pace of work' translates as power output.

If so, and there is a net loss of energy from moving from A to B too rapidly, or too slowly, then there is most likely a happy mean where it moves from A to B at some optimum speed that maximizes net energy gain. And this optimum might be called the natural speed of motion, or the natural pace of work - where the 'pace of work' translates as power output.

forelimb.dcr

forelimb.dcr